By Bill Carey

18 January 2026

For decades, conversations about interior firefighting, risk, survivability, decision-making and tactics have been driven by anecdotes, tradition and emotionally charged reactions to worst-case outcomes. Every line-of-duty death is tragic. When that death occurs during interior operations, the emotional impact ripples quickly through the fire service. Grief, anger, and disbelief are natural responses to loss. But in the hours and days after an interior LODD, another force often takes hold—fear-based commentary that reshapes the narrative before facts are known.

When fear enters the conversation, it encourages generalization rather than analysis. Over time, LODD data becomes an emotional symbol instead of an analytical tool.

Aggregation Without Understanding

One of the most common errors is treating yearly LODD totals or categories as a monolithic dataset. Annual fatalities are mentally combined into a single narrative without examining how deaths are distributed across cause, nature, activity type, recording methods and even specific incident details.

Latest ‘Data’: 10 Years of Interior LODD Data

This approach ignores critical variability. One year may see a higher number of medical events, another a spike in vehicle-related deaths, and another an isolated interior fire fatality. When these differences are reduced in understanding to a single number, context disappears and fear fills the gap.

Availability Bias and Selective Memory

Psychologically, people can overestimate the likelihood of events that are vivid, recent, or repeatedly discussed, through a phenomenon known as availability bias. For the fire service, social media and training anecdotes can amplify this effect by repeatedly highlighting rare but dramatic interior LODDs while ignoring mundane or statistically dominant causes of death.

Availability bias is a type of cognitive bias where people judge the likelihood or frequency of an event based on how easily examples come to mind, rather than on actual data or probability. In other words, if something is vivid, recent, or memorable, we tend to overestimate how common or likely it is.

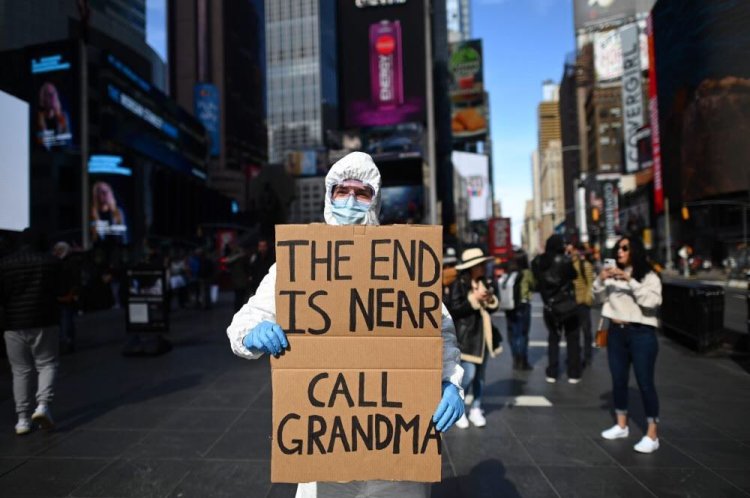

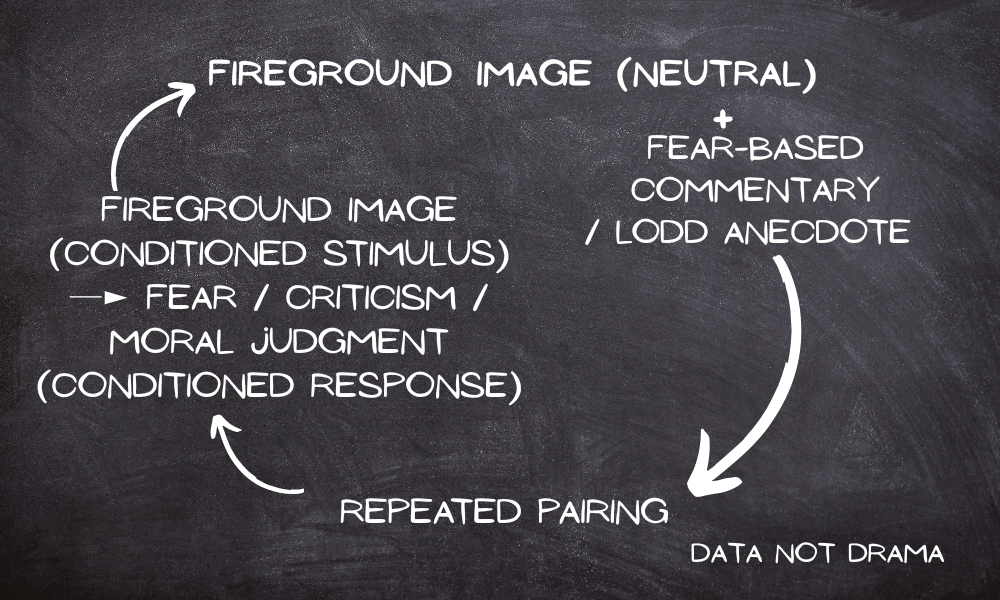

Through social media, picture superiority and availability bias interact in a way that amplifies each other. Picture superiority effect is the psychological principle that humans are much more likely to remember images than words. A striking image sticks in your mind far longer than a written statistic or description. A dramatic fireground photo or video of a firefighter in danger is instantly memorable. That vivid memory is what drives availability bias. Visuals evoke stronger emotions than text alone, which reinforces the perception of risk. Even if an incident is statistically rare, repeated exposure to striking images online makes it feel common.

Over time, firefighters begin to believe interior operations are the primary driver of LODDs, even when year-by-year data shows otherwise. Fear does not come from the data itself, but from which parts of the data are emphasized and remembered.

Emotional Weight Replaces Granularity

Fear thrives where detail is absent. When firefighters are exposed repeatedly to tragic headlines or emotionally framed images, the brain prioritizes emotional recall over statistical accuracy. Instead of remembering what actually happened in a specific incident, they remember how the image made them feel.

Fear and Imagery

Emotionally charged images shared online or in training can often anchor fear in firefighters’ minds and distort how risk is perceived on the fireground, outweighing what the data actually shows.

As a result, single high-profile fireground LODDs can overshadow years in which interior structural firefighting accounted for few fatalities. The emotional impact of one event becomes representative of the entire dataset, regardless of frequency or trend.

Fear Bias and How It Shapes Our Understanding of LODDs

Cognitive psychology explains why fear so easily distorts perception and decision-making:

Availability Bias: Humans overestimate the likelihood of events that are vivid, recent, or frequently discussed. A single dramatic interior LODD, replayed in social media posts or training debriefs, feels more common than it actually is.

Negativity Bias: Negative information has a stronger impact on attention and memory than positive or neutral data. Fatalities trigger stronger emotional responses than near misses or successful risk management.

Hindsight Bias: After an incident, it feels “obvious” what should have been done. This bias makes decisions that were reasonable at the time appear reckless in retrospect.

Emotional Amplification: Fear activates the amygdala, which prioritizes emotional processing over analytical thinking. Even factual LODD data can be filtered through anxiety, producing exaggerated perceptions of risk.

Confirmation Bias: Once fear takes hold, people tend to notice only the data or anecdotes that support their worry, ignoring statistics that would challenge it.

These biases make aggregated LODD numbers feel more threatening than they are and encourage rules, policies, or attitudes based on fear rather than fact. Recognizing these psychological patterns is the first step toward replacing fear with data-driven decision-making.

From Data to Doctrine Without Analysis

When fear shapes how LODD data is misunderstood, it often migrates into policy and training. Departments adopt broad restrictions based on aggregated fear rather than targeted risk controls based on specific causes. Instead of addressing the most common or most preventable factors in a given year, departments react to the most emotionally charged ones, This misalignment can leave firefighters less prepared for the risks they are statistically most likely to face.

Fear feels like awareness, but it is not the same as comprehension. True understanding of LODD data requires disaggregation, examining causes, conditions, timelines and trends year by year. It requires separating frequency from severity and probability from possibility.

When that work is not done, fear becomes the organizing principle. The data is still cited, but it is no longer understood.

The Picture Superiority Effect, Fear and Firefighters’ Perception of Risk

This visual bias doesn’t just distort individual memory—it affects policy, training, and public perception.

Leave a comment