By Bill Carey

7 June 2025

This is the third in a series of articles explaining how imagery and promotion cultivate fear in the fire service. It is recommended to read the previous articles to understand the concepts.

How Did We Become Scared of the Roof? The Visual

The Picture Superiority Effect, Fear and Firefighters’ Perception of Risk

We live in a world saturated with images. From news headlines to social media feeds, visuals often define how we understand events, people and risks. However, what many people do not realize is how profoundly these images impact our emotions, memories, and even decision-making. This phenomenon, known as emotional anchoring through images, helps explain why some pictures stay with us for years, shape our beliefs and guide our actions long after we have seen them.

Defining Emotional Anchoring Through Images

Emotional anchoring occurs when a specific image becomes associated with a strong emotional response, creating a lasting impression in memory (Paivio, 1991; Hockley, 2008). This bond between image and feeling becomes an “anchor” that shapes how we interpret future information or make judgments related to the topic the image represents.

For example, a photo of a child being rescued from a burning building may emotionally anchor someone’s perception of firefighters as heroes. Conversely, an image of a firefighter who died after falling through a roof may anchor a perception of danger around that specific tactic, even if the tactic is statistically rare or safe when properly executed.

This concept builds on the picture superiority effect, a psychological principle that shows people remember images more effectively than words. Emotionally charged images, in particular, are processed rapidly and stored more vividly in long-term memory than written or spoken language.

How Does Emotional Anchoring Work?

Emotional anchoring through images works because of how our brains respond to emotionally significant stimuli. Here’s how the process typically unfolds:

- Exposure to a Vivid Image: A person sees a powerful image often tied to trauma, danger or high emotion.

- Emotional Reaction: The image triggers fear, sympathy, awe, anger or another strong emotion.

- Memory Encoding: Because the brain prioritizes emotionally charged events, the image becomes anchored in memory.

- Judgment Influence: Later, when the person faces a decision or similar situation, the anchored image influences how they perceive the risk, value, or danger involved.

This process often happens unconsciously. People rarely realize that a past image is shaping their present-day thinking.

What Are Some Real-Life Examples of Emotional Anchoring?

- 9/11 Attacks: The image of planes striking the World Trade Center became emotionally anchored to terrorism for many Americans. It affected not only public sentiment but also national policy, security measures and even how people viewed others from certain ethnic or religious backgrounds.

- War Photography: Iconic photos from the Vietnam War, such as the “napalm girl” (Nick Ut’s Pulitzer-winning 1972 image) or images of soldiers under fire, shaped public opinion against the conflict. These photos didn’t just report facts, they anchored national emotions and redefined how Americans viewed the war.

In the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, images of flag-draped coffins, detainee abuse at Abu Ghraib, and bombed civilian areas reshaped policy debates and troop morale.

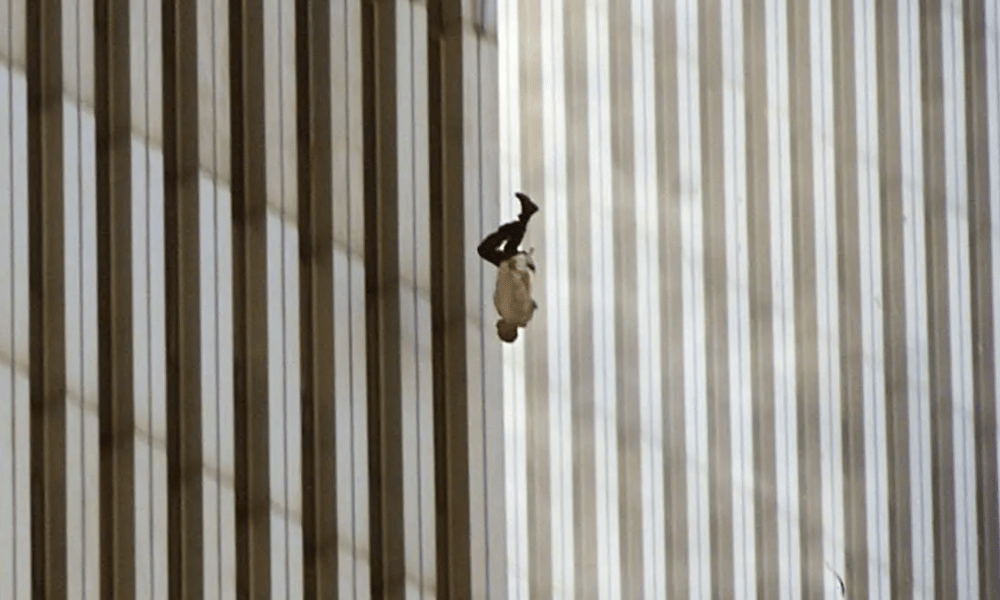

The “Falling Man” Photo

One of the most haunting examples of emotional anchoring is the “Falling Man” photograph, captured by Associated Press photographer Richard Drew on the morning of 11 September 2001.

The image shows a man, later believed to be Jonathan Briley, falling headfirst from the North Tower of the World Trade Center. It freezes a split second of tragic motion, a lone figure suspended against the vertical lines of the building, as the nation and the world watched the towers burn and collapse. The photo, stark and deeply human, became emotionally anchored in the public’s memory of 9/11. It came to represent not just the horror of that day, but the deeply personal, impossible choices faced by those trapped above the impact zones.

However, the image was also the subject of intense criticism and controversy. Many newspapers that initially published it were met with public backlash, with readers calling it exploitative, insensitive, or too disturbing. Some argued that it violated the dignity of the individual and the privacy of his death. As a result, the photo was quickly withdrawn from many front pages and rarely republished in mainstream outlets afterward. This controversy reflects the raw power of emotionally anchored imagery: it evokes feelings that can be so overwhelming that they lead to censorship, denial, or selective memory.

Despite the criticism, the “Falling Man” remains one of the most enduring visual symbols of 9/11. It challenges viewers to confront the personal realities behind large-scale tragedy and serves as a powerful example of how a single image can carry enormous emotional and cultural weight. Emotional anchoring ensures that, for many, this one photograph continues to define part of the experience of that day, often more viscerally than words or statistics ever could.

[Andrew Keiper’s article, “An Ethical Analysis of the Falling Man” probes the ethics behind publishing the “Falling Man” photo.]

In all these cases, the images didn’t merely report facts; they defined narratives. They became proxies for truth, often overpowering nuanced discussions or statistical evidence. The same mechanism operates within firefighter culture, where emotionally vivid photos can override a decade’s worth of incident data or NIST fire modeling.

Why Do I Need to Understand Emotional Anchoring?

Understanding emotional anchoring is important because it helps explain why people sometimes make decisions that don’t align with logic or data. Anchored emotions often override rational thought. A person may fear flying due to dramatic images of plane crashes, despite knowing it’s statistically safer than driving. Similarly, a firefighter may avoid a proven tactic not because of poor training or lack of skill, but because of an emotionally anchored memory of a past tragedy.

This kind of influence can affect:

- Public opinion and media narratives

- Policy and leadership decisions

- Risk perception in high-stakes professions

- Cultural attitudes and biases

What Should I Do When I Become Aware of Emotional Anchoring?

The key to managing emotional anchoring isn’t to ignore images or suppress emotion. Instead, it’s to become aware of when an emotionally charged image is influencing your thinking. Ask:

- Where did I first form this opinion?

- Was it based on data, or a vivid event or image?

- Does this image represent a common reality or a rare exception?

- How might this emotional anchor be affecting my choices?

By examining the sources of our emotional reactions, we can better align our perceptions with reality and avoid being unconsciously steered by powerful, but unrepresentative, imagery.

Moving Toward Visual Literacy and Contextual Awareness

The solution isn’t to reject imagery altogether, but to teach firefighters—and decision-makers—how to interpret images in context. Visual literacy should be part of firefighter training, just like hazard recognition or building construction. Every compelling image should be accompanied by:

- Context (What happened before and after?)

- Probability (How common is this scenario?)

- Applicability (Does this relate to your typical fireground?)

By anchoring visual memory to evidence-based practices instead of fear-based narratives, departments can better align risk perception with actual risk.

Emotional anchoring through images is a natural and powerful part of how humans learn, remember and feel. But like any strong force, it must be understood and navigated wisely. Whether you’re a decision-maker, public servant, educator or everyday media consumer, recognizing the influence of emotional anchoring helps you think more critically and act more deliberately.

The lead photo is the Waldbaum’s supermarket fire in Brooklyn, New York on 2 August 1978. 24 firefighters were on the roof. When a collapse occurred, 12 firefighters fell through and six were killed. Fire Department City of New York photo.

I have been assigned a new email address by the Commonwealth.

How do I update my email address?

[cid:3401cd85-57e3-4b9a-a774-609017c1834f]

Thomas Cook – MBA, CFO, CTO

State Fire Commissioner

Pennsylvania Office of the State Fire Commissioner

phone: (717) 651-2201

Follow us on Facebookhttps://www.facebook.com/PAOSFC

LikeLike

You can send it using the https://data-not-drama.com/contact/ contact page.

LikeLike