This is the second in a series of articles explaining how imagery and promotion cultivate a fear about vertical ventilation that is not found in other firefighting tasks. “How Did We Become Scared of the Roof? The Visual” is the first.

By Bill Carey

28 April 2025

Firefighting is a profession of immediacy. It demands rapid decisions, often made in chaotic environments where sensory overload is common. But what if some of those decisions—about what’s dangerous and what’s not—aren’t based exclusively on training or data, but are affected by images in our memory?

This isn’t just a philosophical question. The psychology of images—and how they dominate thought and emotion—needs to be understood. The picture superiority effect, the availability heuristic, and emotional memory all play roles. Add in social media, a culture of decision-shaming, and institutional decision-making shaped by fear, and you begin to see how firefighting is being silently reshaped—not by what is happening, but by what is seen happening.

When Images Speak Louder Than Experience

In firefighting, few decisions carry as much weight—or spark as much controversy—as those involving vertical ventilation. Traditionally a beneficial tactic, it’s now often viewed with doubt or fear. Why has this shift occurred? A key factor may be rooted not in strategy or statistics, but in psychology—specifically the picture superiority effect. This cognitive bias shapes what we remember, what we fear, and how we act in life-threatening environments.

The Picture Superiority Effect: A Cognitive Shortcut

The picture superiority effect is a psychological phenomenon where images are more likely to be remembered than words. This idea stems from the dual-coding theory (Paivio, 1971), which argues that visual and verbal information are stored in separate channels in the brain. When something is both seen and described, it is more likely to be retained.

- Nelson, Reed, and Walling (1976) found that pictures are over 65% more memorable than words.

- Shepard (1967) showed that people could remember 98% of pictures even after days, compared to only 10-20% of textual information.

In high-stress environments like firefighting, this has profound implications. The images that dominate our training, media coverage and social feeds heavily influence what we remember as “dangerous.”

Fear on the Roof: A Case Study in Visual Distortion

In How Did We Become Scared of the Roof? Carey, 2023, I explored how vertical ventilation—cutting openings in roofs to release heat and smoke—has become increasingly controversial, not necessarily because the tactic has changed, but because the imagery surrounding it has.

Key insights from this include:

- Visibility Bias: Roof ops are easily visible from outside and above, making them far more likely to be captured on camera.

- Imagery vs. Data: Photos of roof failures and near-misses go viral; meanwhile, other high-risk tasks like hoseline advancement or interior search are rarely photographed and therefore seem less dangerous.

- Emotional Anchoring: Images of burning roofs, firefighters falling through decking, or roof collapses are seared into the collective mind, overshadowing statistics that show vertical ventilation, when done correctly, reduces interior temperature and improves survivability.

This visual bias doesn’t just distort individual memory—it affects policy, training, and public perception.

War Photography and National Memory: Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan

This phenomenon isn’t unique to firefighting. It has shaped entire wars.

Vietnam War: The First Televised War

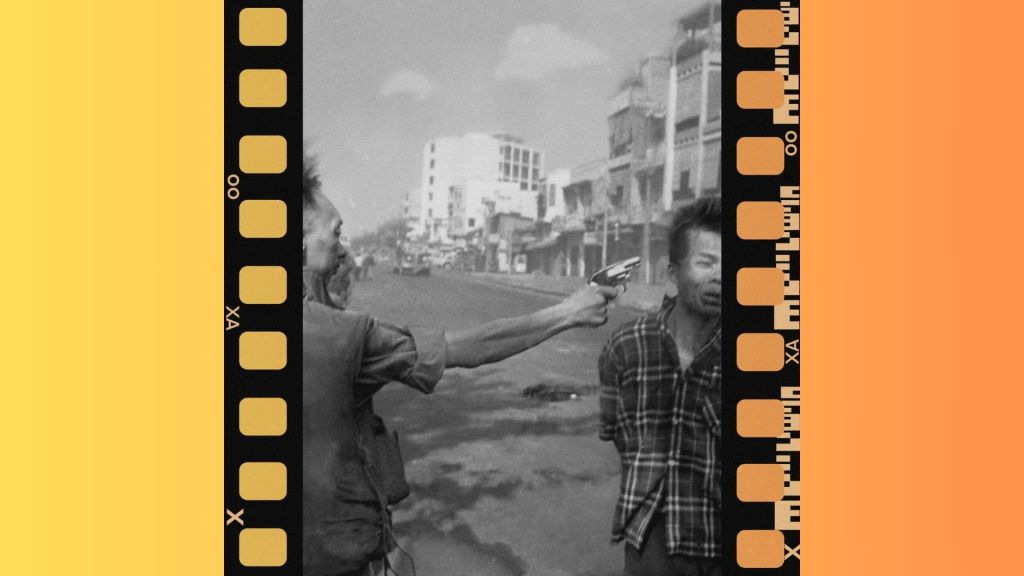

During the Vietnam War, combat footage and photography brought the horrors of war directly into American homes. Images such as:

- The execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém in 1968

- The “Napalm Girl” photo of Phan Thi Kim Phúc

- The body bags at Da Nang

These images weren’t just snapshots—they shifted public sentiment. Support for the war plummeted not necessarily because the facts changed, but because the images forced an emotional reckoning. Americans could no longer view the war in abstract terms. The picture superiority effect transformed distant conflict into personal revulsion and catalyzed the anti-war movement.

Iraq War: Abu Ghraib and the Power of Exposure

In Iraq, the 2004 Abu Ghraib photos—depicting prisoner abuse—had an explosive impact. What had been whispered about in diplomatic and human rights circles was suddenly undeniable. The graphic, undeniable visual record forced policy shifts, investigations, and long-term reputational damage to U.S. military operations. Again, the availability heuristic kicked in: when people thought of the Iraq War, they thought of those photos, even though they represented a fraction of operations.

Afghanistan: The Cost of the Invisible War

In contrast, much of the Afghanistan War lacked strong visual documentation—especially in its early stages. As a result, public engagement was lower. When images did emerge—like the 2009 photos of soldiers’ caskets returning to Dover AFB—they triggered renewed scrutiny and criticism, prompting policy shifts in the Obama administration, including ending the ban on photographing military coffins.

These examples show how images don’t just reflect reality—they often redefine it. The same is true on the fireground.

Fear Amplified: The Role of Social Media and Cognitive Biases

In today’s media environment, social media acts as a feedback loop for fear.

- Confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998): Once firefighters believe roof operations are too dangerous, they’re more likely to seek out and remember media that confirms this belief.

- Availability heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973): The more vivid and recent an example of roof-related danger, the more likely we are to overestimate its frequency or severity.

A single viral photo of a firefighter plunging through a roof—regardless of the rarity of the incident—can leave a longer-lasting impression than years of safe, successful ventilation practice.

Visuals and the Emotional Brain: Neuroscience at Play

From a neurological standpoint, images—especially fear-inducing ones—activate the amygdala, the brain’s emotional processing center.

- Dolcos, LaBar, and Cabeza (2004) found that emotionally charged images create stronger, longer-lasting memories and influence decision-making more than neutral ones.

- This emotional memory can override rational analysis, particularly in high-adrenaline professions like firefighting.

So even if the data supports a certain tactic, the emotional residue from a powerful image may prevent its use. This is not weakness—it’s human neurology. But it’s one that must be acknowledged and addressed.

A Historical and Cultural Lens on Fire Imagery

I also reflected on how religious and cultural imagery of fire—as punishment, as destruction, as wrath—deepens our primal fear of certain fire-related scenarios. He connects this to classic American religious texts, such as Jonathan Edwards’ Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, where fire imagery served as a fear-based control mechanism.

Modern fire imagery may not be religious, but it’s no less emotionally charged. Burned PPE, collapsed roofs, and melted helmets are potent symbols—often circulated without context, nuance, or reflection.

Recalibrating Risk Perception: Toward Data-Driven Culture

To combat the distortions caused by the picture superiority effect and media amplification, the fire service needs to recalibrate how it talks about and teaches risk.

Recommendations include:

- Contextualizing Imagery: Use real-life images in training, but pair them with context—what happened, why it happened, and how it could be prevented.

- Balanced Representation: Incorporate visuals of other high-risk tactics (interior fire attack, VES, RIT operations) into instructional material.

- Data Over Drama: Shift cultural emphasis toward incident data, tactical outcomes, and operational analysis, not just anecdotal or viral moments.

- Critical Thinking and Debiasing: Train firefighters in basic psychology and decision science to help them recognize when their judgment is driven by emotion over evidence.

Conclusion: From Spectacle to Strategy

The picture superiority effect teaches us that seeing is remembering—but not always understanding. In the fire service, where life and death can hinge on decisions made under pressure, we must be vigilant about what we internalize and why.

Images are not inherently misleading—but without critical analysis, they can hijack our memory, amplify fear, and shift culture. It’s time to reclaim our perception, resist fear-based narratives, and build a fire service grounded in data, not drama.

References

- Carey, B. (2023). How Did We Become Scared of the Roof? The Visual. Data Not Drama

- Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and Verbal Processes.

- Nelson, D. L., Reed, V. S., & Walling, J. R. (1976). Pictorial superiority effect.

- Shepard, R. N. (1967). Recognition memory for words, sentences, and pictures.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability.

- Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises.

- Dolcos, F., LaBar, K. S., & Cabeza, R. (2004). Amygdala and memory: Modulation of encoding and retrieval.

Your recommendations are good ones. Hopefully, there are no firefighter training programs that don’t use them, or haven’t been using them for the last 20 years or so. Yes, context-free pictures and descriptions of dramatic incidents can reinforce the potential danger of firefighting – for non-firefighters, and those who are subject to industry training that is fear-based – again, hopefully very little of that exists. If it does, it’s certainly not in my experience in the southwest where I worked, or anywhere else I ever travelled. Your examples of how these things work psychologically are informative, but there seems to be an intent to do the opposite – characterize the thinking that there is inherent danger in many of our operations – especially in roof operations – as some psychological ploy to scare firefighters into fearing roof ops and not use them in a timely and effective manner based on science AND data. I plan to read “How Did We Become Scared of the Roof”. I didn’t know we had become scared of it, and hope to be enlightened rather than puzzled.

LikeLike